109

108

K

alamkari or Qalamkari, is derived from the Persian

words

qalam

(pen) and

kari

(craftmanship). It

refers to printed cotton fabrics, in combination with

pen work.

Produced in many parts of India, from ancient times,

these were said to have been traded throughout the

world. Cotton dyed with mordants was discovered

at excavations at the Indus Valley as the fabric was

preserved fused to a silver jar. This dates dyed cotton

fabric to roughly 3,000 BC.

The printed fabrics of Gujarat and southern India were

used by traders and merchants as currency, largely

to trade spices from Southeast Asia and Indonesia.

Historical accounts state that Kalamkari paintings

were in demand in these regions for use in rituals and

ceremonies. They were also traded with theMiddle East

and Europe. The discovery of the Fostat textiles drew

attention to the early history of Indian printed fabrics.

While different Kalamkari traditions developed

throughout India two places in Andhra Pradesh

were well-known for the art: Srikalahasti and

Machilipatnam. While the former is known primarily

for its free-hand drawing with a charcoal stick for the

outlining of patterns, in the latter there was a greater

reliance on blocks.

Machilipatnam is also known to have made Kalamkari

for the Iranian market, with its designs and motifs

influencing those made in Iran. The painted temple

hangings of Srikalahasti were known as

waratapani

,

while Kalamkari of Machilipatnam, which was made for

export became known by the Persian word

kalamkari

,

that is pen work.

The art form steadily declined during colonial rule and

post independence Kamaladevi Chattopadyaya and

Jasleen Dhamija helped establish a government run

Kalamkari training centre to encourage the craft as part

of the All India Handicrafts Board’s textile revival project.

They were helped in this by the designer Nelly Sethna.

The Kalamkari traditions in Iran and India did not grow

in isolation, there were connections between the two

regions via the Kingdom of Golconda where the ruling

kingMuhammadQuli Qutb Shah (1580-1611 AD), was

of Persian origin and carried out his court in the Persian

Safavid style. This meant that several Persians were

settled in the region, with some working as artisans.

Persian influence is certainly evident in the Kalamkari

pieces fromMachilipatnam.

In Iran, the main centre for Kalamkari was Isfahan. The

ones made here are known for their muted tones and

highly bleached backgrounds, as well as the artist’s

creativity in drawing out both floral and figurative

motifs. Artisans who used the

kalam

were called

kalamkars

as against block printers who were called

chitsaz

. They drew their outlines with iron acetate with

brushes made from animal hair. The thicker ones were

made from horsehair, and finer ones, used largely for

calligraphic details, were made from cat hair.

KALAMKARI

60

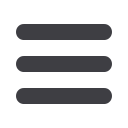

PICTORIAL KALAMKARI WITH

MUSICIANS AND DANCERS

ISFAHAN, IRAN, CIRCA 1930

Handspun and handwoven cotton, hand drawn

and painted, natural dyes

59 x 95.5 in (150 x 243 cm)

$ 6,065 - 7,580

Rs 4,00,000 - 5,00,000

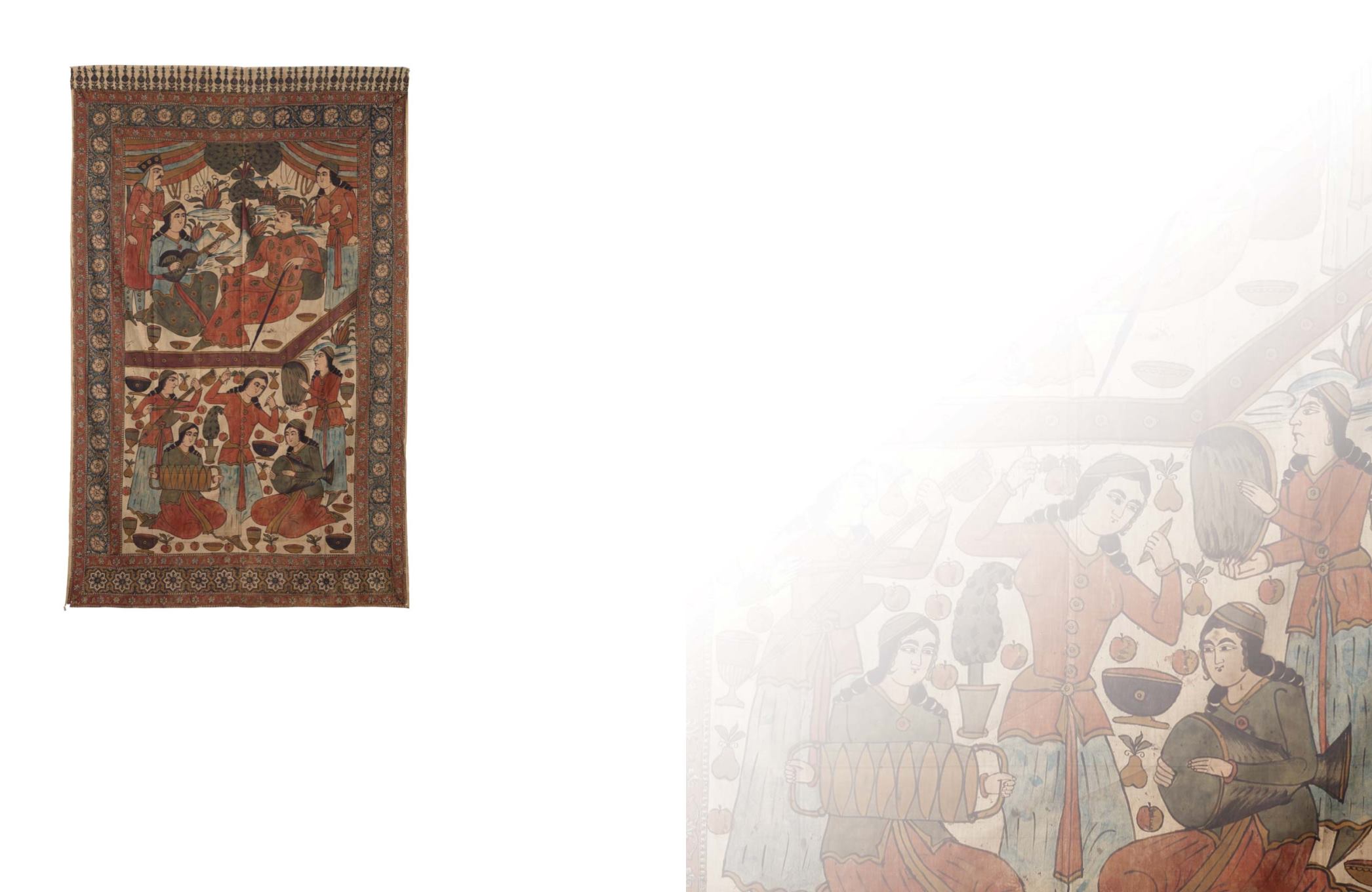

A man, probably a courtier or

even a king, reclines on a pair of

green bolsters as he is entertained

by a group of young women.

Singing and dancing, playing

musical instruments, the women

are dressed in long skirts with

short, long-sleeved, fitted blouses

and long belts that accentuate

their slender waistlines. The

young man is dressed in a long

robe painted with

botehs

and

decorated with ornate buttons.

On his head, he wears a striped

turban. In his left hand he holds

a slim, black walking stick and in

his right, a wine glass. The other

man to the left, whose features

make him look older, is possibly

his retainer; his tunic is shorter

and is not decorated.

The scene is probably one of

an outdoor picnic, a popular

pastime in Iran, and suggested

by the background in the upper

register with itsmountains, plants,

and a single tree in the centre. A

lone building on the right of the

tree, perhaps the young man’s

residence hints at a stately home

or a palace, referencing his status.

Enclosed by three borders of

flowers scrolling off a single

vine, the present lot has a

three-dimensional feel to it. The

voluminous curtains on either

side of the tree, at the top, make

it reminiscent of a theatrical

scene. While figurative pictorial

scenes were prevalent in Iran,

not that many are known today

outside public collections.