20

21

placed sparsely, keeping the ground empty. Petals and

leaves were outlined in a contrasting colour, a feature

that contributes to the intricate delicacy of the shawl.

The colour palette also changed, as synthetic dyes

replaced natural ones. Early shawls were bright and the

number of colours used minimal, with some woven

in not more than two or three colours. By the 18

th

century and certainly by the 19

th

, the shawls were a

burst of colours and the weaver's ingenuity was visible

in the number of bobbins, each wound with a different

colour, he could manipulate while weaving.

There are many theories about the origin of the shawl.

Commonly shared beliefs say that Syed Ali Hamadani,

who brought Islam to North India, first introduced it

in the region in the 14

th

century bringing weavers from

Iran. He was followed by Badshah Zain-ul-Abidin in

the early 15

th

century who brought master weavers

from Samarkand. This is confirmed by his historian,

Pandit Srivara, who mentions that new looms were

introduced by the master weavers of Central Asia.

Another theory is that the movement of Sufis from

Central Asia, many of whom were accomplished

weavers, brought this art to Kashmir. The eminent art

historianDr.MotiChandracontends that the technique

was prevalent during Vedic times, as references can be

traced in the

Arthashatra

, mentioning the Kashmiri

poet Kshemendra (990-1070 CE) who testified to

the existence of shawls. However, the historian Janet

Rizvi believes that it was a local craft that developed

in Kashmir itself – one that went on to be both

encouraged and patronised by the Mughal rulers, first

Akbar and then Jehangir. She maintains that references

to Hamadani and Zain-ul-Abidin are rather ambiguous

and not grounded in any historical textual references,

nor do they corroborate with any oral traditions.

Central Asia is probably the region where this

technique originated. It possibly owes its origin to the

ancient technique of the

soumak

, a speciality of the

tribal weavers of Central Asia, who wove with non-

continuous weft in the twill weave. As the colour

changed, the thread was left loose to float at the back.

Though no examples of shawls of this period have

survived, yet there is mention of woven fabrics being

sent as gifts to the Mameluks, Sharifs of Mecca, and

the rulers of Khorasan and Turkestan among others.

Shawls were largely bought or commissioned by

royalty and affluent families; some were also made

specifically for the priestly class. They were coveted

not only in India but further in Iran, Poland and

Russia, Europe and England. However, spiralling taxes

on weavers and the emergence of the Jacquard loom

in Europe and England led to the partial demise of

the shawl industry in India. The

kani

almost died out

with only one or two master weavers remaining in the

village of Kanihama in the 20

th

century. While revival

efforts have succeeded in reinventing the Kashmir

shawl, the original pieces can never be replicated.

The interest in collecting Kashmir shawls largely began

after Independence, as collectors and museums from

abroad started to make purchases, exhibitions were

held and publications became available. In India, the

Kashmir shawl has always been a collector’s item, as

much a sign of prosperity and status as that of being

a distinguished textile scholar. Jasleen Dhamija’s

collection includes some fine examples of pashmina

shawls and articles of clothing. Some of these were

acquired in Kashmir itself, others from intrepid

shawlwallahs

from the region who used to visit Delhi

in the cold winter months. One exceptional shawl in

the collection belonged to Jasleen Dhamija’s mother.

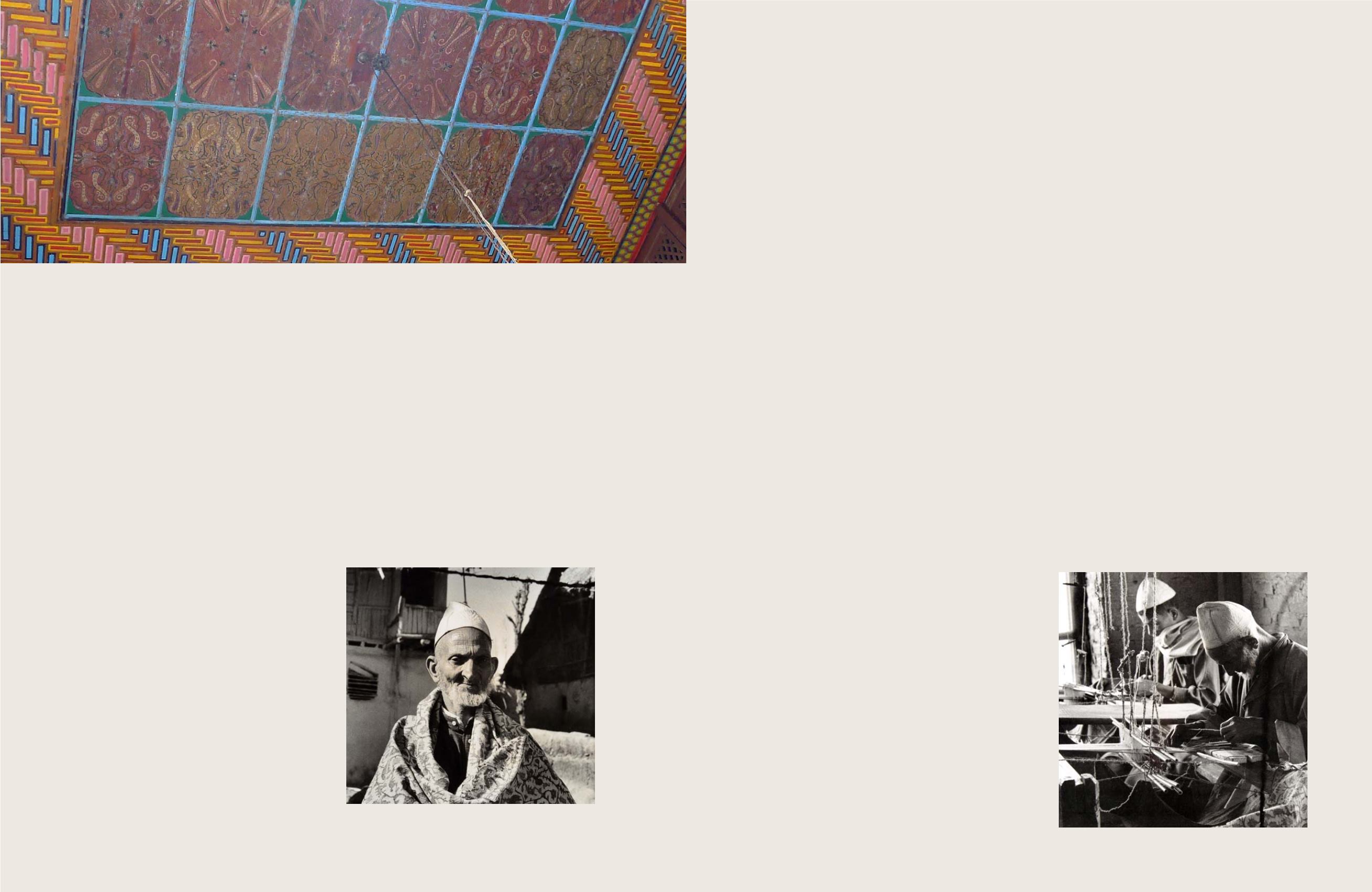

Kadir Lala weaving a

kani

shawl

at his home in Kanihama

K

ashmir has always been recognised for its highly

refined arts – papier-mâché, woodcarving

and carpet weaving – but it is the pashmina shawls

that are synonymous with the region. Bearing

finely embroidered and intricately woven designs,

their softness and warmth, rich colours, exquisite

and elegant designs have appealed to discerning

individuals for centuries.

Recognised as a luxury fibre,

pashm

commands some of

the highest prices in the world of textiles because of its

extreme softness, elegance, and lustre. The fibre comes

from the fine undercoat of goats reared by nomadic

pastoralists living on the high plateau of Changthang in

Eastern Ladakh and Western Tibet. The goat has been

called by several names: shawl goat, pashmina goat and

changra

(northern goat). It is a result of the intense cold

on the windswept plateau and the high altitude that

pashm

of a high quality is produced.

The Kashmir shawl has been used as a shoulder-

mantle, turban, waistband or

patka

(sash). The fabric

has also been used to make saris, floor coverings and

prayer mats, as well as stitched garments such as men’s

chogas

,

jamas

(robes), long skirts and capes. Kashmir’s

shawl industry involves the work of many people

from the pastoralists who herd the pashmina goat, to

traders who bring in the fibre, to dyers and designers,

weavers and needle-workers. Women are involved in

the processing of the fibres, mainly cleaning, carding

and spinning it into fine yarn.

The delicacy and charm of a Kashmir shawl reflects

the creativity of the designer and the wide palette

of colours they work with. Designs varied from early

shawls that had narrow borders and contained small

floral motifs where the ground colour was visible, to

more elaborate patterns with large motifs that swept

across the entire body of the shawl with broad

pallavs

(decorative ends). Many of the early shawls were largely

inspired by the Mughal-style single-flower motif,

SHAWLS

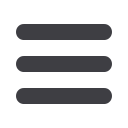

Kadir Lala in Kanihama, wearing the

kani

shawl for which he got the

National Award from President Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, 1967

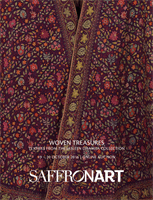

Ceiling of the Shah Hamdan mosque shows shawl patterns, Srinagar, Kashmir

© Monisha Ahmed