development schemes. Making traditional crafts

and engaging in any livelihood related to them was

severely punished. With the change in political

policies beginning in the 1980s and '90s there has

been a resurgence of nationalism and the growth

of a new market economy has helped reinstate

traditional customs. For

suzanis

it has meant a revival,

with age-old skills of embroidery flourishing again

and reinventing themselves in different forms. It was

also during this period that Jasleen Dhamija worked

for the United Nations Development Programme

(UNDP) in Central Asia with a focus on Uzbekistan.

Her work concentrated on the revival of

suzani

,

S

uzanis

are remarkably vibrant flower-strewn

cloths fromCentral Asia. Exquisitely embroidered,

they served as cradle covers, wrappers for gifts, bed

canopies, niche curtains, tent decorations and wall

hangings. The word ‘suzani’ is derived from

suzan

,

the Farsi word for needle. Embroidered cloths were

made famous in cities along the Silk Road: Bokhara,

Samarkand, Shakhrisabz, Tashkent and Ferghana, in

Central Asia.The earliest known

suzanis

date from the

mid-18

th

century, though the tradition of embroidery

was most certainly practised before that. Among the

fragments of textiles found at excavations at Pazyryk

in Siberia, were materials with embroidery patterns

with chain stitch similar to those used today. By the

19

th

century, embroiderers showed an unsurpassed

skill in the artistry of composition and needlework.

Women of the family traditionally embroidered

suzanis

; they were made for domestic use and were an

essential part of a bride’s dowry. All girls were taught

to sew from an early age and a girl’s

suzanis

were

proof of her needlework skills and marriageability,

and a demonstration of her economic value to her

husband’s family. The extraordinary beauty and

brightness of the

suzani

was said to reflect a mother’s

aspirations for her daughter’s future. These dowry

textiles were considered to have magical properties

related to protection, fertility, and the birth of

progeny, bringing positive energy to the bride’s new

home. Their presence at weddings, as bridal canopies

and marriage bed-sheets, was prominent and each

stitch represented the bride’s hopes and dreams of

her happiness.

Making a

suzani

involved many women in the

household, especially the larger ones. It began by

loosely joining narrow widths of fabric together so that

a

kalamkash

or designer, could draw the pattern over

the surface and assist in the selection of colours. The

strips were then taken apart and shared among the

women for the actual embroidery. It was not unusual

to find that the panels did not match perfectly when

SUZANI

reassembled or that the two halves of a piece were not

symmetrical. The women often left a small portion of

the composition empty as a gesture implying that only

Allah could be capable of perfect creation.

Flowers and leaves are principal ornaments in

suzanis

, not surprising in a long-established

agricultural economy where gardens around homes

are filled with flowers. Most are highly abstracted

and their identity consequently uncertain. Some are

recognisable however as carnations, irises, roses and

tulips. Stylistically, the flower motifs on

suzanis

are

often reminiscent of Ottoman embroidery, Persian

embroidery and Indian palempores commonly

known as

chintz

(painted and dyed cotton wall-

hangings or coverlets), which is indicative of both

the longevity of the tradition and the cross-cultural

influences that formed them.

During the Soviet period many traditional crafts were

discouraged or banned, with both men and women

recruited for the Soviet industrial and agricultural

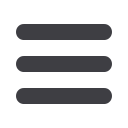

Suzani

hanging on a balcony in Karshi, Kashkadarya, 1996

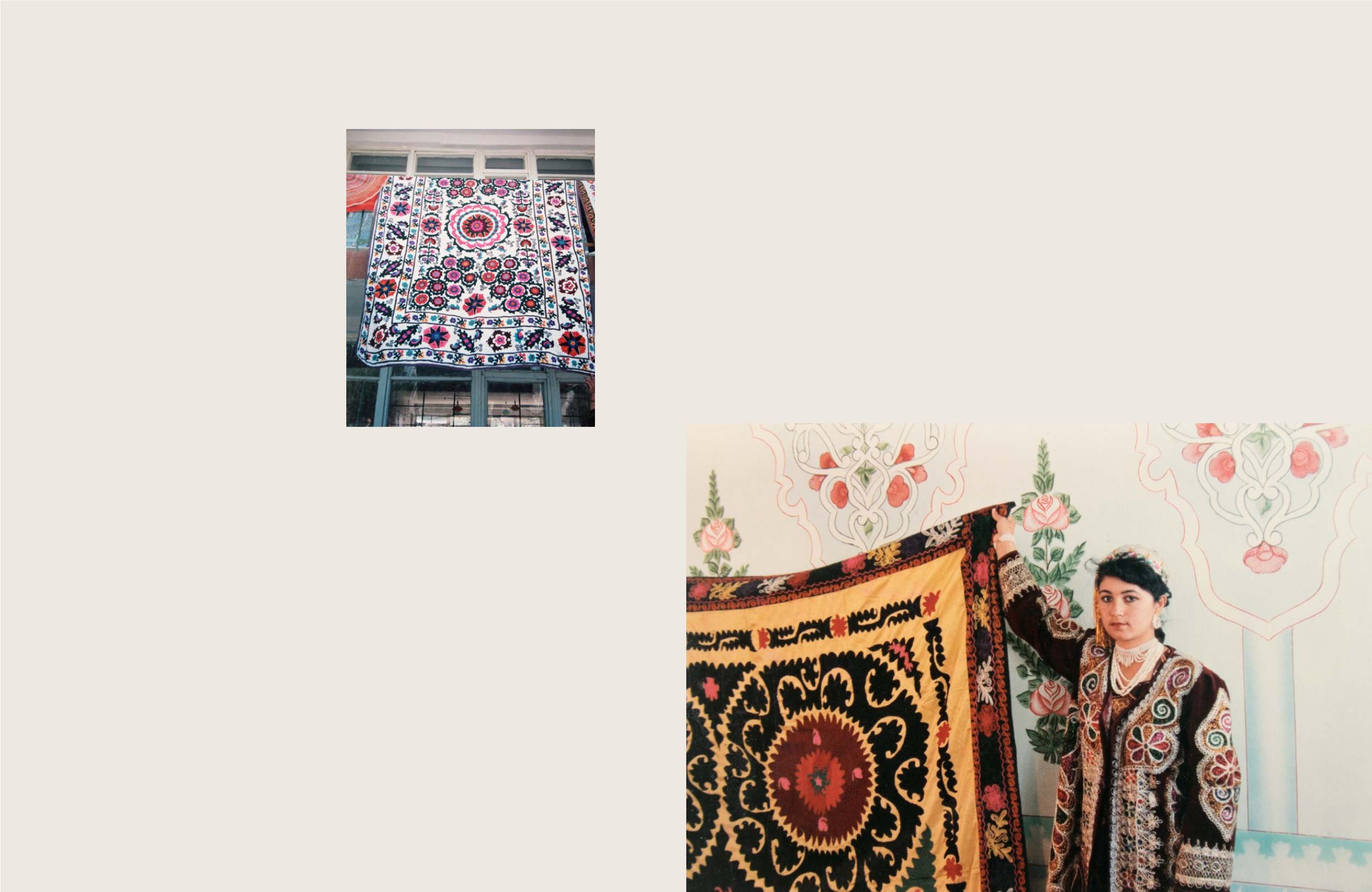

Young Uzbek bride with the

Suzani

made by her mother. Uzbekistan,1996

as well as other textile arts such as

ikat

weaving,

felt making and research into natural dyes. During

this time, she acquired some old

suzanis

that were

representative of the different regions of Central Asia.

One spectacular large wall hanging from Tashkent,

with multiple sun-moon motifs or

palyak

, has hung

on the wall of her home for years.

Suzanis

made

before the 1920s and 1930s are prized by collectors

the world over, desired and acquired by the most

ardent of textile connoisseurs.