40

Saffronart | Evening Sale

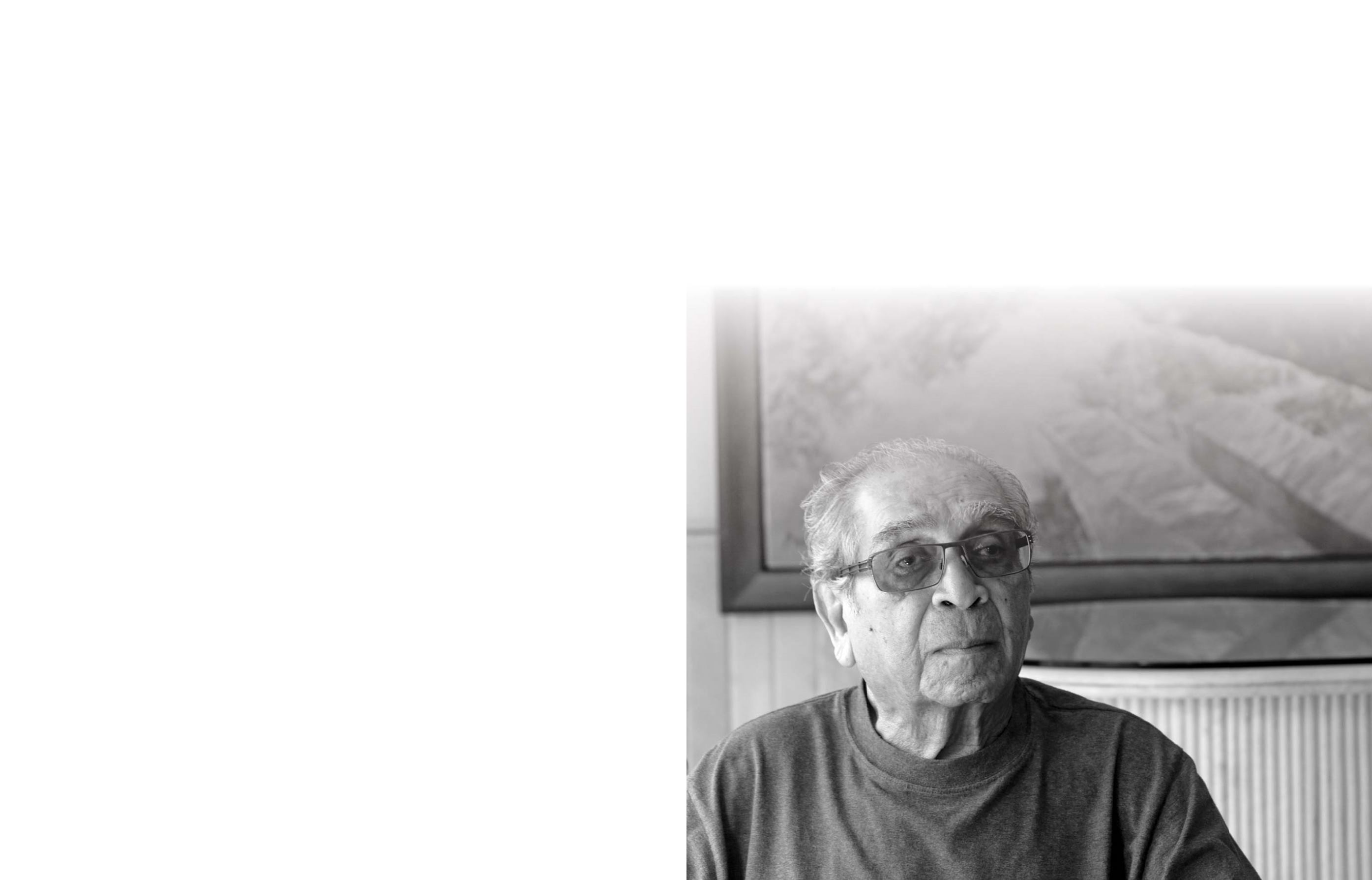

AKBAR PADAMSEE IN CONVERSATION

WITH MEERA GODBOLE‒KRISHNAMURTHY

,

Editor‒in‒Chief, Saffronart

23 May 2016, Mumbai

Akbar Padamsee has been called a “painter’s painter.” In conversing with Padamsee, it becomes clear that this phrase does not

quite capture his deeply intellectual and analytical mind and his art. Padamsee is an “artists’ master.” It is as though he visualises

objects in space as deconstructions and then reconstructs them on the canvas in simplified form, so that the viewer may

better understand the structure of line, form, colour, and tone that he has seen in his mind. Padamsee is constantly “working

something out,” as he said during our conversation, speaking of his grey paintings. In 1969 he made an eleven minute silent film

titled

Syzygy

, based on number theory, which he says is his source for all permutations of mapping space. He doesn’t find the

need for words to explain any further, esoteric as the concept may seem to the viewer. (People have recommended taking an

aspirin before watching this film, but we watched it together after only a cup of tea.)

Underneath each of his later luminous Metascapes which leap off the canvas with their incandescent glow, is a clearly mapped-

out construction of multiple point perspectives, horizon lines and vanishing points situated far beyond the canvas frames,

complex enough to give an architect pause. He then paints over this deconstructed reconstruction–I use this term because

the entirely rigorous construct comes from Padamsee’s memory, not from any existing reality in the physical world as we know

it. But to Padamsee, the painted‒over scaffolding underneath is still visible. There is a methodology to his paintings that is

hidden in plain sight.

Greek Landscape

is especially significant against this background and in light of Padamsee’s subsequent

five decade long career as an artist. We see in it the early workings of the master trying to “figure something out.” Hidden in

shades of grey are the earliest markings of a way of looking, understanding, seeing, and recreating. The limited palette of black,

white and grey adds precision to the process without distracting from the pure analysis of form and space, background and

foreground, light and shadow. It is not surprising that Krishen Khanna saw in it the work of a genius and acquired the painting

immediately upon seeing it. It takes a true artist to recognise a master.

MGK:

Tell me about this work.

AP:

This was a very large painting, you know, 12 feet long. I had a special wood frame made for it so I could stretch out the

whole canvas. Fortunately the courtyard in the building I lived in—in Juhu—was large enough to accommodate the

size of this canvas. It was too hot during the day with the bright sunlight, so I worked at night, with lights. There was a

dog that used to come and sit with me while I painted. Every night, he would just show up, sit there quietly, and then he

disappeared after I was done. He was called Pandu. But I called him Cézanne.

MGK:

Perhaps he was channelling the spirit of Cézanne as you “constructed” your painting?

AP:

Oh, I don’t know.

MGK:

So then you didn’t roll the canvas out and work in sections, you had the entire stretch unfurled on the frame? Was it flat

on the ground? Did that change the way you moved and used the brush?

AP:

No, the canvas was not on the ground, it was vertical. There were poles in the courtyard, so the frame was upright, tied

to the poles. I maybe painted it in segments, but I was always constructing the whole painting.

MGK:

And this is plastic emulsion with brushes?

AP:

Yes, it is the plastic emulsion used to paint buildings and homes. I would buy the paint in large tins. Black and white. At

the time, the paint I wanted was not available in India. And the paint one got was often glossy, but I was lucky to find

a man who sold the non‒glossy matte, plastic emulsion. When I told him I was using it for a painting, he said I would

need brushes and brought out the painters’ brushes he had. The broad ones with the thick bristles. So I bought those

from him too.

41

MGK:

Why did you decide to do such large scale works at that time?

AP:

I don’t know, I just did. I was working something out. The other grey works were smaller canvases, nudes, figurative

works. There were four that were of this large scale.

MGK:

Why the restriction to black, white and grey? Was it to understand something about light and shadow, or tonal structure?

Did working at night help in that sense?

AP:

I used black and white and grey because I wanted to understand what colour means. It is a thought process. To

construct a painting, you have to understand colour, space, object. It didn’t matter if it was day or night, because the

thinking happens in the mind.

MGK:

Did you miss colour when you did the grey paintings?

AP:

No, because I knew that after this, I would use colour in my next paintings. It was there.

MGK:

And why is this named Greek Landscape?

AP:

(Laughs) Krishen [Khanna] gave it that name! It is just a landscape. I’ve never even been to Greece!

MGK:

Are any of the landscapes from the Grey series set in a real place? Or are they imagined constructions?

AP:

They are all from my imagination. None of the cities or buildings are of any real place. They are all from my memory.

MGK:

How long did you work on this ‘Greek Landscape?’ It must have been quite strenuous work, given the scale, and the fact

that you only worked at night.

AP:

Yes, it was unusual. It took me about a month, with breaks. It’s signed 1960. That’s when I completed it.

Akbar Padamsee in his studio, Mumbai, 2016

© Eesha Patkar