28

29

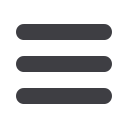

The present lot in the drawing room of the de Trafford family home, Beaulieu, Hampshire

Signed copy of book included with this lot

SIR DERMOT AND

PATRICIA DE TRAFFORD

The de Trafford family trace their roots to Lancashire in

England. In 1967 Dermot de Trafford (who later became the

head of the family as Sir Dermot de Trafford) and his wife

Patricia visited India to attend a conference.Theymet Jehangir

Sabavala in what was then called Bombay. He presented them

with a book of his work, published by Sadanga, inscribing it

to the collectors. This book is included as part of this lot. A

friendship developed and subsequently, they purchased the

present lot,

The Star That Beckons

directly from him. The

painting was taken to their country house, fondly called The

House in the Wood, near Beaulieu in Hampshire. It has hung

in the drawing room ever since.

JEHANGIR SABAVALA

A RECKONING BEYOND THE “ISMS”

MEERA GODBOLE‒KRISHNAMURTHY

Editor‒in‒Chief, Saffronart

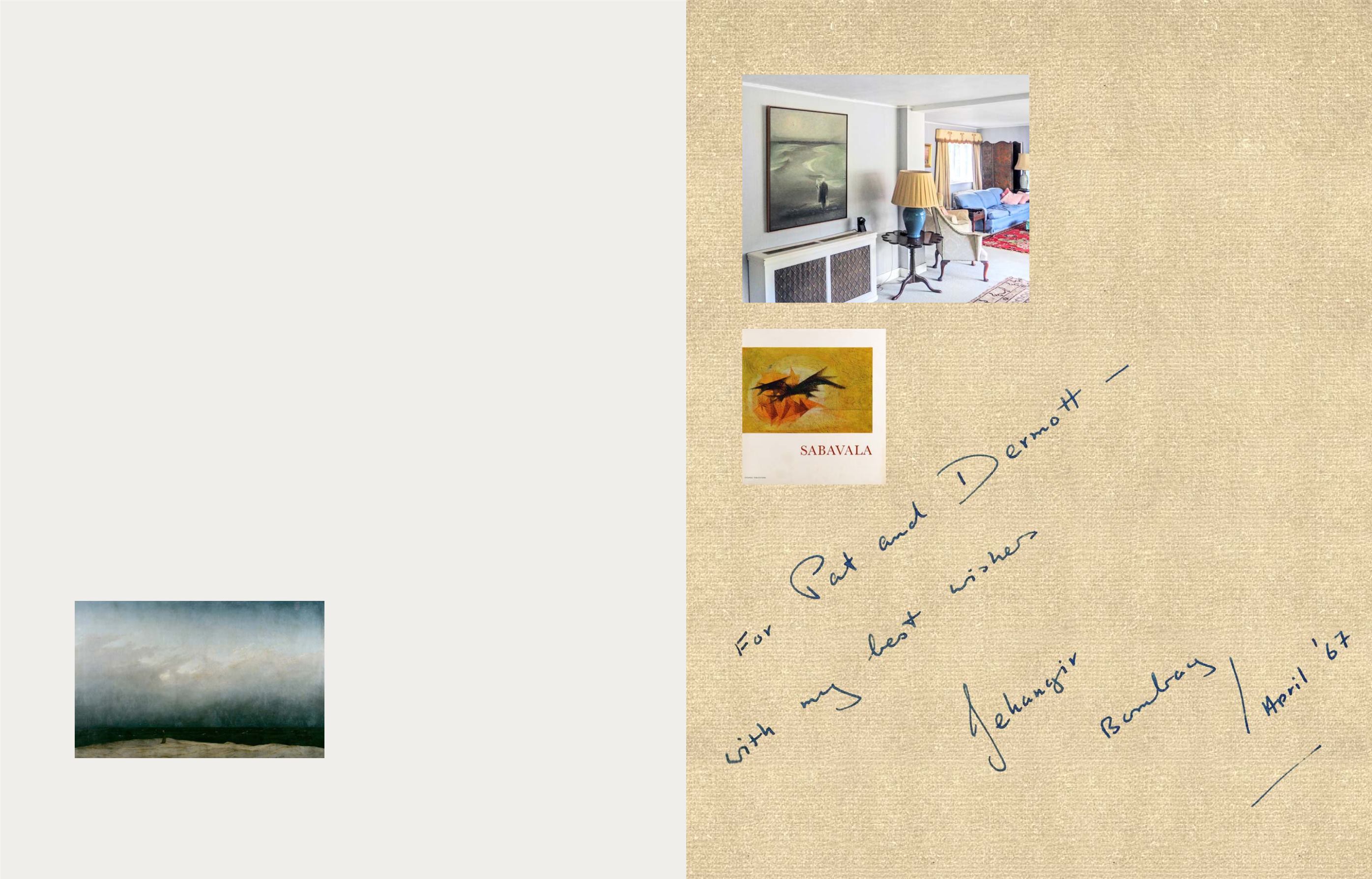

Caspar David Friedrich,

The Monk by the Sea

, 1808‒1810

Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin

Wikimedia Commons

Jehangir Sabavala was an iconoclast, an unusual persona

on the Indian art scene. His interests lay in a myriad of

“isms,” from Cubism to Existentialism, from Romanticism to

Spiritualism, and yet, he resisted being tied down to any

particular philosophy. In spite of his decidedly European

art training and intellectual leaning, as the film‒maker

Arun Khophar put it, “People who only knew him as a

‘Westernised' person, did not know how deep was his

knowledge of the Indian landscape, its trees, rocks, ravines

and waterfalls.” (Arun Khopkar, “Colours of Absence,”

The Hindu Magazine

, 10 September 2011, online) His art

remains in a space that is universal and timeless, primarily

because he dealt with the concerns of the human

condition. He stated, “I think, as a painter, in all those hours

spent alone, you are not only thinking of the painting. You

are thinking of yourself, of death, of mortality, of tragedies

and happiness.” (Artist interview with Yashodhara Dalmia,

quoted in Anindita Ghose, “In His Eternal Quest, Sabavala

Applied Precepts of Cubism,”

Live Mint

, 3 September 2011,

online)

The 1960s and ’70s were a period in which he had begun

to break away from the formalism of structured Cubism

in order to integrate allegory and certain nuances of

mysticism into his work.

The Star that Beckons

, painted in

1968, embodies many of Sabavala’s overriding concerns. In

a revealing statement to the American art critic George

Butcher in 1964, Sabavala wrote, “No longer am I satisfied

with the juxtaposition of planes, the search for rare colour,

the almost total denigration of the unpremeditated. It is

the intangible which is now my goal. Space and light, and

an element of mystery begin to permeate my canvasses.”

Not unlike the Star in the title of the present lot, it was

Light which beckoned Sabavala. A luminescence began to

permeate his serene canvases.

European traditions of landscape painting made a

distinct impact on Sabavala’s understanding of form and

composition. Unlike the English and French Romantic

painters who focussed on pastoral scenes or on taming

the wilderness that was Nature, German Romanticism was

unique in its almost cerebral desire to understand nature.

This inquiry must have resonated with Sabavala’s quest.

Caspar David Friedrich’s iconic 1808‒1810 painting titled

The Monk by the Sea

offers insight into Sabavala’s search

for divinity. In both paintings, a lone figure, the

Rückenfigur

,

is placed with his back to the viewer, on a lonely journey

into a vast, still landscape with a horizon which seems

to be a mere stand‒in for infinity. There is no scale, no

structural reference to suggest any notion of humanity or

narrative possibilities. As a result, one is left contemplating

the immensity of nature. Sabavala masters the art of

minimalism in this canvas, creating an atmosphere that

inspires awe.

Whether or not the journey is religious, as connotated by

the beckoning star, or secular, in keeping with his portrayals

of pilgrim in exile, Sabavala’s subtle canvas presents a world

of intrigue and introspection that lies beyond the merely

mortal structures of the many “isms” that frame such

conversations.