98

99

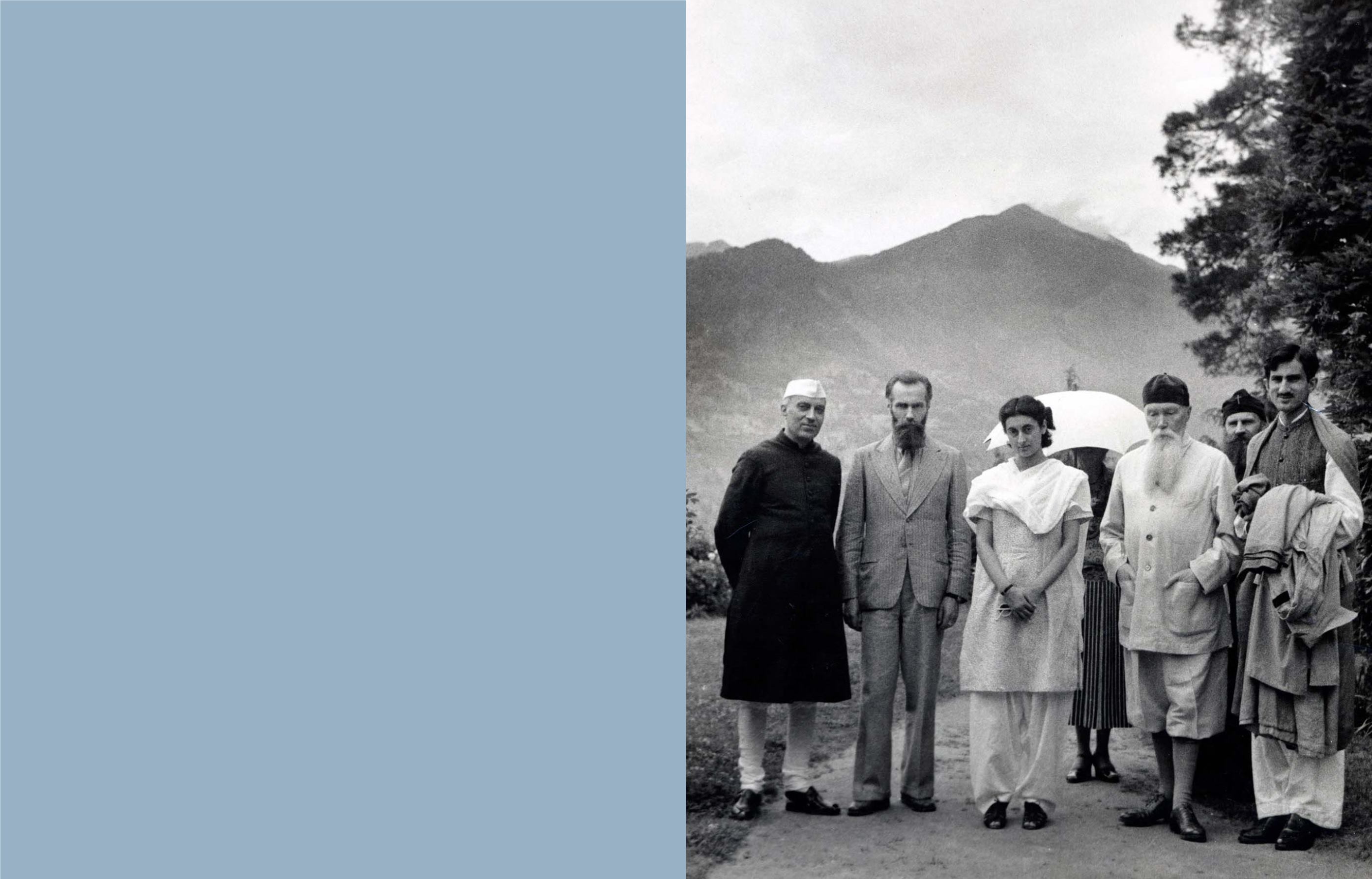

(Left to right): Jawaharlal Nehru, Svetoslav Roerich, Indira Gandhi, Nicholas Roerich, Helena Roerich (with umbrella), Naggar, India, 1942

Image courtesy of Nicholas Roerich Museum, New York

Roerich’s association with India began in his childhood, with

an old family painting of a majestic mountain that he admired.

He later discovered that it was the famous Kangchenjunga in

the Himalayan range, a mountain he would later trek to and

be inspired to paint. Quoting from the Chinese book,

Wei

Tsang T’u‒Shih

, in his diary in 1924, he writes, “The luster of

the mountain peaks is equal unto emerald. Verily the beauty

and perfection of all objects make this place incomparable.”

(

Altai‒Himalaya: A Travel Diary, Part I India

, New York: Nicholas

Roerich Museum, online)

Born Nicholas Konstantinovich Roerich on 9 October 1874 in

St. Petersburg, Russia, Roerich was raised in an upper middle‒

class family which interacted with influential people in Russia’s

vibrant art and cultural scene. He developed an interest in

archaeology and prehistoric artefacts, and showed a propensity

for drawing at a young age. He wished to pursue a career as an

artist, but his father, a lawyer, did not consider it an appropriate

profession. Eventually reaching a compromise, Roerich enrolled

simultaneously at the Academy of Art, and St. Petersburg

University to study law.

Over the next few years, Roerich immersed himself in the music,

arts and theatrical spaces of Russia. He served on the editorial

board of the

World of Art

magazine, a publication founded by

his contemporaries, and later was the secretary of the School

of the Society for the Encouragement of Art. During this time,

Roerich sought to revolutionise the system of art training by

bringing all the various fields of art under one roof, and giving

his faculty freedom to design their own curriculum. “The cross‒

fertilization of the arts that Roerich promoted was evidence

of his inclination to harmonize, bring together, and find

correspondences between apparent conflicts or opposites in all

areas of life. This was a hallmark of his thinking, and one sees it

demonstrated in all the disciplines he explored. He constantly

sought to break down compartmentalization, and, indeed, even

in his own art he defied categorization and created a universe

uniquely personal.” (Nicholas Roerich Museum, online)

By the first two decades of the 20

th

century, Roerich had

established himself as an eminent artist not just in Russia, but

in parts of Europe as well. At this time, a combination of factors

led the Roerichs, which included his wife Helena, and two sons

George and Svetoslav, to leave the country. With Roerich’s

deteriorating health, and the dangerous political atmosphere in

the years preceding the Russian Revolution of 1917 and World

War I, the Roerichs set for India.

Arriving in Bombay, (now Mumbai) in December 1923, the

artist and his family set upon a tour of India’s historic sites and

cultural centres and met with several artists, writers, scholars

and scientists including the Tagores and Bose Sen. Roerich kept

meticulous records of all the sights, the people he met and his

impressions of those encounters. Their journey culminated

in Sikkim, and it was evident that Roerich was drawn to the

spiritual and sociological elements of the culture in addition

to the physical magnificence of the Himalayan mountains. The

family continued on an expedition across Central Asia, covering

Chinese Turkestan, Altai, Mongolia and Tibet for the next five

years. Prompted by an anthropological interest in the “ancient

origins of human civilisation,” (Maria Zinger‒Golovkina,

“Painting. Late 19

th

to the early 20

th

century,” Irina Volchenkova

ed.,

Masterpieces of the State Tretyakov Gallery: Russian Art from

the 12

th

to early 20

th

century

, Moscow: Red Square Publishers, p.

114)—an intellectual and aesthetic curiosity that was evident

even in his earlier paintings of Russian landscapes, folklore and

mythology—Roerich’s aim was to study the life and culture of

these uncharted territories and its inhabitants.

The Roerichs eventually returned to India in 1928 and settled

in the Kullu Valley in the Himalayan foothills. Together they

founded the Urusvati Himalayan Research Institute, a centre

for the study of the Western Himalayas and adjacent regions,

which incorporated the learning from their expeditions.

Roerich’s Himalayan‒inspired art was deeply informed by a

sense of spiritual exploration. In many of the paintings from this

time, “we can see philosophical concepts and ideas giving birth

to visual images, and the splendor of Northern India providing

the physical setting.” (Nicholas Roerich Museum, online) His

paintings capture not only the physical magnificence and

ethereal atmosphere, but also evoke the spirit of the Himalayas,

as seen in the present lot. They are a symbolic reflection of his

own spiritual journey and the strength of character he acquired,

facing the physical challenges of his arduous expeditions.

Roerich is a highly revered figure internationally, and most of his

paintings are in public institutions in the US, Russia and India.

The present lot is a most significant, rare work to be offered at

auction in India.