68

69

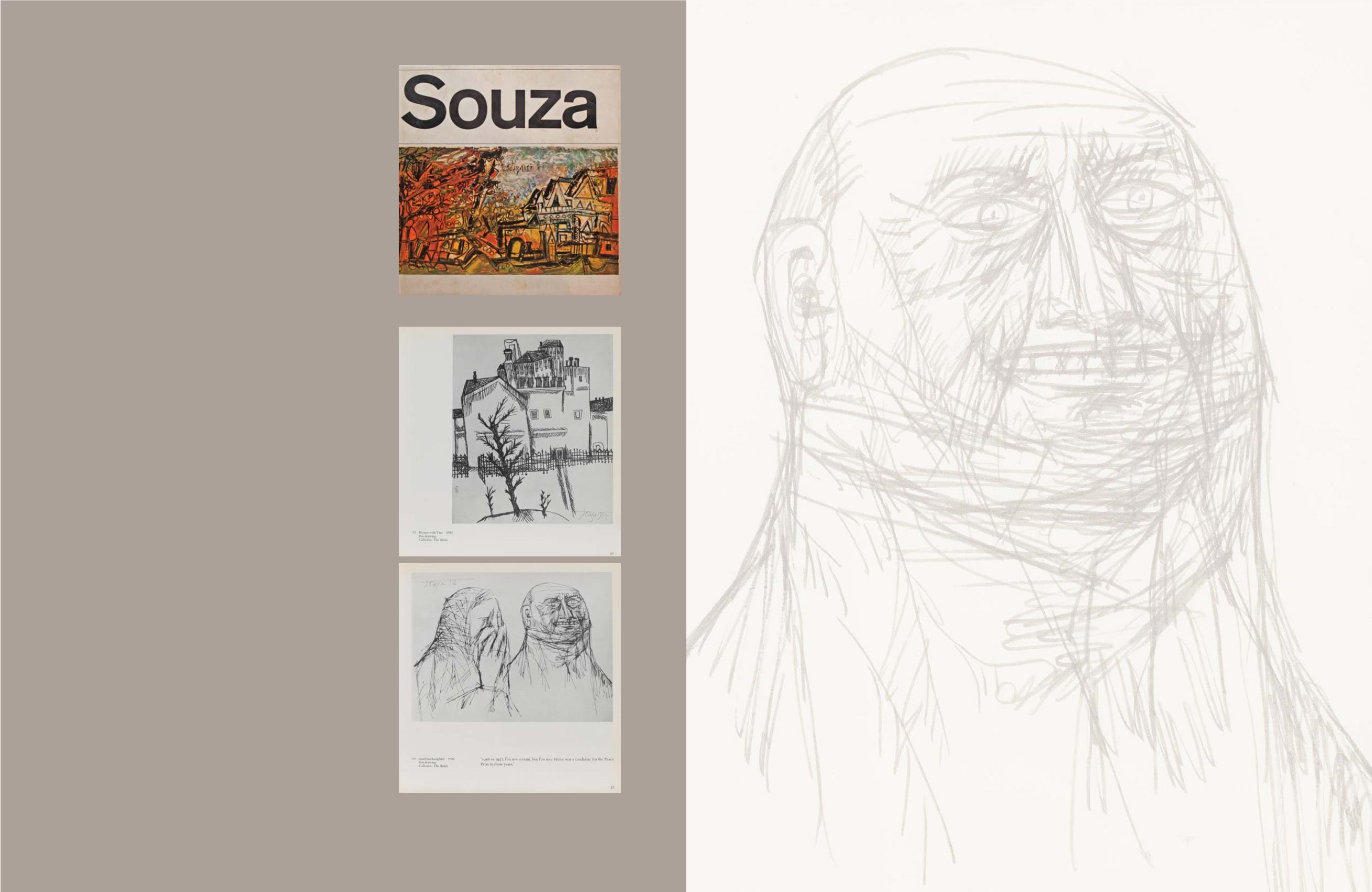

According toMullins, “Figurative art presents noproblems

for Souza because he has succeeded in creating images

that are entirely personal, yet recognisable at the same

time.” (Mullins, p. 36) Lot 47, made in 1956, is a poignant

example of Souza’s heads. A year before, he created a

suite of six ink drawings titled

Six Gentlemen of our Times

,

depicting men who appeared like “a combined portrait

of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, sly, evil and at the same time

terrified.” (Geeta Kapur,

Contemporary Indian Artists

,

New Delhi: Vikas Publications, 1978, p. 27)

These anatomically distorted faces—with the eyes placed

too high on the forehead, teeth bared and gnashing, and

marked by a fury of criss‒crossing lines—are emphasised

in the present lot as well. At first glance, the drawing,

which is titled

Grief and Laughter

, appears to show two

faces expressing the universal emotions of “grief”, as

seen in the remorseful expression of the figure on the

left, and “laughter” in the smiling face of the figure on

the right. But further scrutiny reveals that the drawing is

not so straightforward. The “laughter” of the right figure

seems transfixed in horror, and the wide‒eyed, smiling

expression borders on surreal. However, as Mullins puts

it: “Souza’s imagery is not a surrealist vision – a self‒

conscious aesthetic shock – so much as a spontaneous

re‒creation of the world as he has seen it, distilled in the

mind by a host of private experiences and associations...

They are full of apparent contradictions: agony and wit,

pathos and satire, aggression and pity. Their impact is

certain, but few people are able to explain what has hit

them.” (Mullins, p. 39)

T

he following lots (48 and 49) were once part

of the personal collection of British writer and

art critic Edwin Mullins, and were featured

in his seminal 1962 monograph

Souza

—a book still

considered critical to the study of the artist’s oeuvre.

A leading authority on art, Oxford‒educated Mullins

spent his career as the art critic for

SundayTelegraph

and

Daily Telegraph

and as a cultural television presenter

for the BBC from the 1960s through the 1980s. In

that time, he covered important developments in art,

within UK and globally, wrote famously about artists

such as Van Gogh, Georges Braque and Alfred Wallis,

and historical accounts of various cultural events.

Mullins' work led him to interact with many artists

of that time, from Salvador Dali, Barbara Hepworth

and Henry Moore, to India’s Souza, who was living in

London at the time.

As Mullins notes, between 1949 and 1955 Souza had a

difficult time making his career as an artist in London,

often shuffling between galleries carrying enormous

paintings only to have them rejected. At the same

time, he studied drawing at the Central School of Art,

giving him reason to continue residing in England.

Living in a single roomwith his wife and baby daughter,

“There was not much space for non‒essentials, and

he [Souza] recalls how a next‒door neighbour once

complained that he had been throwing drawings in

the communal dustbin. Apparently her children had

been rummaging, and had found them. They were

drawings which, she said ‘were not quite nice’, and

she accused him of being a corrupting influence on

the young. Souza was rather flattered. It was the first

time anyone in England had taken notice of his work.”

(Edwin Mullins,

Souza

, London: Anthony Blond Ltd.,

1962, pp. 21, 23)

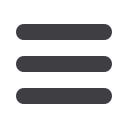

Lot 48, dated 1953, was sketched during Souza’s early

years in London and appears to be a quaint scene of

the cityscape composed in simple rectilinear lines.

Souza employs his signature cross‒hatching technique

in this drawing, including the parallel lines which give

the appearance of harpooning spears. These serve to

create an ominous mood, which intensified in Souza’s

later work.

Lots 49 and 50 were once part of Edwin Mullins’ private collection

and were published (pp. 51, 57) in his seminal 1962 monograph

on the artist.

Cover of Edwin Mullins,

Souza

, London: Anthony Blond Ltd., 1962